Born in Utah in 1874, C. D. Schettler came from a wealthy and slightly eccentric family. His father, Bernard Herman Schettler, came of age before the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (also known as the Mormon Church) renounced ‘plural marriage’ in 1890 and therefore took three wives. However, following both the Church’s renunciation and a federal prohibition of ‘unlawful cohabitation’, Bernard Herman chose to live only with his first wife and set up separate households for the others.1 He had seven children with his first wife. For some reason (or perhaps for no reason at all), the children were named alphabetically. The first child was August Bernard (A.B.), who died in infancy, followed by Cornelius Daniel (C. D.), and so on, until the final child Quince Rudolph.

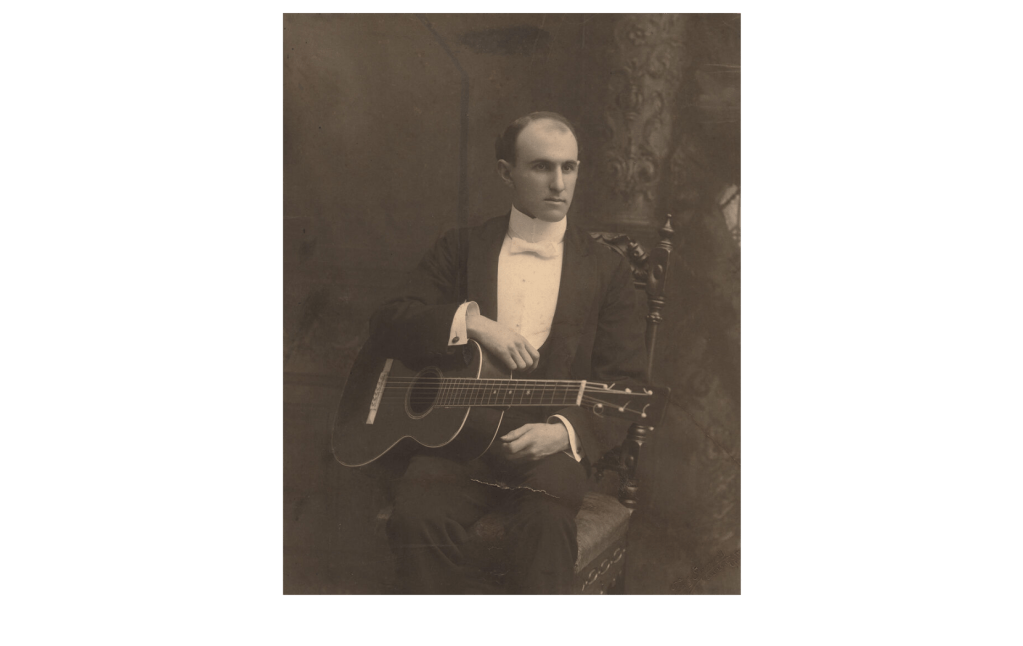

Bernard Herman was a banker, and as C. D. was the eldest surviving son it was assumed he would take over his father’s business. However, his musical activities were increasingly taking over. In addition to giving performances, he rented a studio and become a renowned teacher. Eventually, music would become his full-time occupation and he would establish himself as one of America’s foremost guitarists.

As a member of Mormon Church, he went on a mission to Germany when he turned eighteen. He then studied the guitar for three years in Munich, Vienna, and Berlin. It was unusual for an American guitarist to receive European training, and it likely helped to set him apart on his return to America.2 His first achievement was taking first prize at the Denver Eisteddfod in 1896. An ‘Eisteddfod’ is a Welsh competitive festival of the arts, which Schettler presumably entered on account of his mother being Welsh.3 He played Mertz’s Fantasia on the Merry Wives of Windsor — Mertz was the guitarist whom Schettler most admired. The prize was a rather minor achievement, especially given that the other six finalists failed to show up,4 making Schettler’s victory certain. But as a canny self-promoter, Schettler keenly advertised his success.

A reviewer of his Eisteddford performance wrote that,

[Schettler] has what is known among guitar players as a “good right hand,” and the rapidity of many of the movements which he is capable of executing is as marvelous as it is pleasing to the ear. The guitar is pre-eminently an instrument of modulation, if it is anything, and Mr. Schettler has the rare talent of producing and controlling the sweetest harmonies of this lovely instrument.5

In addition to many performances across the United States, Schettler gave many performances in Germany.6 His playing there was well received:

People generally laugh about the guitar, but the way Mr. Schettler controls his instrument entitles it absolutely to a place as an artist’s instrument among stringed instruments. His virtuosity is point-blank phenomenal, and with it he shows a wonderful fulness of tone and clearness in technique that one could believe he was listening to a harp concert.7

Two decades later, in 1928, a German article still remembered Schettler’s concerts in Germany, writing that he was ‘celebrated everywhere as the foremost guitar soloist’.8

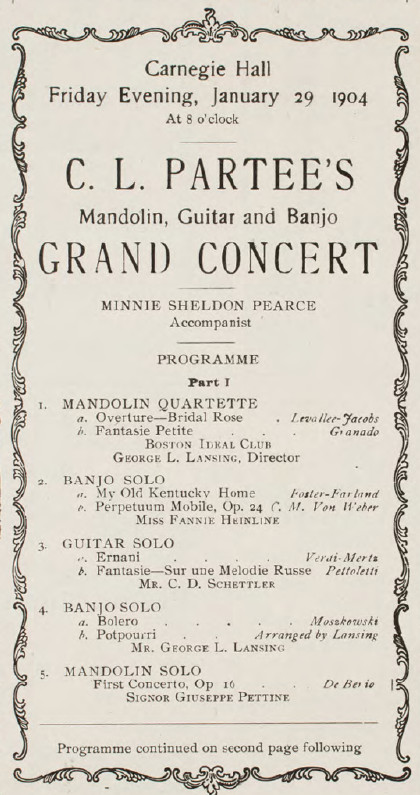

Schettler’s greatest claim to fame is that he was the first guitarist to perform at Carnegie Hall, as a part of a banjo, mandolin and guitar concert (the BMG movement was a popular phenomenon at the time). However, Schettler was the first only by a hair: the guitarist William Foden also performed pieces in the second half of the concert. The ‘grand concert’ was followed by a ‘grand banquet’, lasting from 11.30pm to 5.30am and consisting of twelve courses. It was reported that Schettler travelled specially for the concert from Berlin.9

As with most American guitarists, Schettler followed Carcassi’s method. However, like a number of young American players, he adopted two notable ‘innovations’: he did not rest his little finger on the soundboard, and he held his guitar the ‘progressive’ way,10 which is to say sans footstool, with the lower bout resting on the right leg and the instrument held quite upright, in imitation of the banjo, whose technique served as inspiration to many guitarists. He used gut strings (unlike some American guitarists who were beginning to use metal strings, if only for the top string), which he would tune down a semitone to help preserve them. And of course, like nearly every American guitarist (and banjoist) at the time, he played without nails.11

Schettler was resolute about the guitar’s validity as a concert instrument: ‘a skilled performer ought to have no difficulty in being heard by an audience of 500 or 1,000 in a church or theater of ordinary size.’12 Schettler strongly believed that the guitar could be equal to the violin or cello, and wrote despairingly of how

quacks swam in our cities, where a few dollars are to be made, and frequently those who cannot execute a scale correctly, know nothing whatever of exercises, and have for their complete repertoire the “Spanish Fandango” and sometimes “Sebastopol,” put themselves up to be complete masters of the instrument.13

In 1904, his father’s bank went under and the Schettler family lost not only their wealth but also their reputation. The father had embezzled approximately $45,000 (about $2 million in today’s money). Possibly because of this disgrace, between then and 1920 there is almost no information about Schettler. His musical work evidently continued, however, and come 1920 he was a well-established teacher in Salt Lake City — primarily on guitar and cello, but also mandolin, banjo, Hawaiian guitar, and ukulele. He also became a cellist in the Utah Symphony.

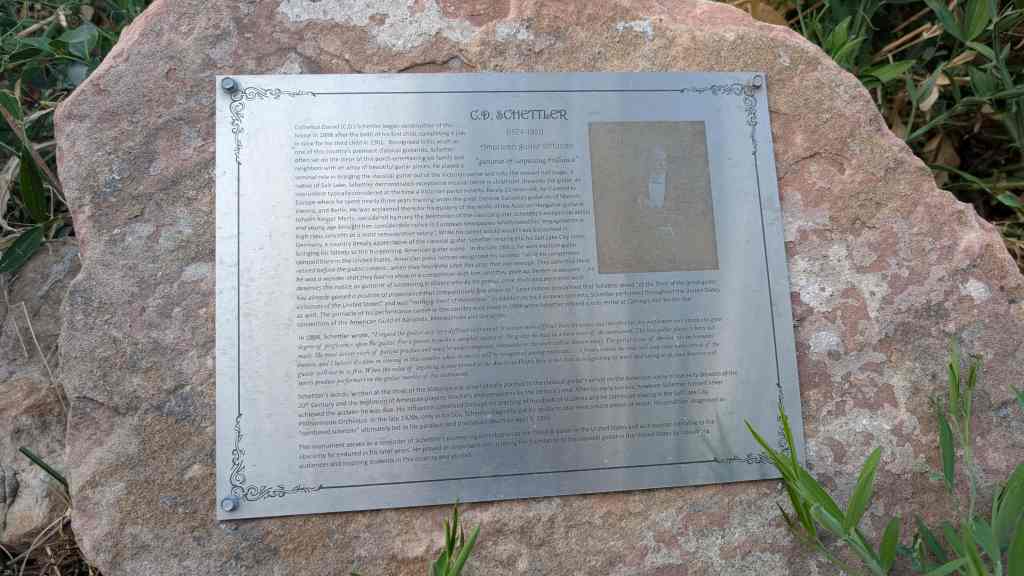

By the mid-late 1920s he was no long able to play even simple pieces, suffering from what may have been muscular dystrophy, and was confined to a wheelchair. In 1927 he experienced what was then described as a ‘nervous breakdown’14 and died in 1931. Sadly, except for a short complimentary paragraph about him in Domingo Prat’s Diccionario in 1934, I cannot find evidence of posthumous recognition. That is, until a few years ago when a plaque was placed outside his house:

I am indebted to the President and Executive Director of the Utah Classical Guitar Society, David Norton, who kindly sent me the research he conducted into Schettler in the early 1990s. This article mostly relies on the letters, clippings, and other sources that David sent.

- N. Turner, letter to David Norton, 29 February 1992. ↩︎

- Noonan 72 ↩︎

- Norton, ‘The Life and Times’. ↩︎

- Salt Lake Tribune, 7 September 1896. David Norton recalls a story that the other contestants were intimated after hearing Schettler play — was the only classically-trained guitarist among them — and they therefore all bailed out. ↩︎

- Daily News, Denver, September 1896, quoted in Cadenza, 5.5 (1899), p. 18. ↩︎

- Schettler was also a member of the International Union of Guitarists, possibly owing to his travels in Germany. See PSG, 13, 1947, n.p. There were three attempts were made to form this Union: in 1877 in Leipzig, in Munich in 1899, and in 1947 in Italy. The first two were rather abortive; the third more successful. Schettler’s grand-daughter wrote in a letter to David Norton (8 March 1992) that Schettler attended classes in Germany with a young Segovia, but the dates make this highly unlikely. ↩︎

- The Nachrichten, 4 August 1903. ↩︎

- Die Gitarre, 9.3/4 (1928), p. 26. Schettler’s concerts in Germany became overshadowed by Luigi Mozzani’s not long after. ↩︎

- BMG, 1.7 (1904), p. 101. ↩︎

- Schettler,’ The Art of Guitar Performing’, The Cadenza, 7.1 (1900), p. 13. ↩︎

- Myron A. Bickford, ‘Hints on Guitar Study’, The Cadenza, 11.10 (1905), p. 32. ↩︎

- Norton, ‘The Life and Times’ ↩︎

- Schettler, ‘Reflections of a guitarist’, The Cadenza, 5.2 (1898), p.7. Spanish Fandango and Sebastopol were two of the most popular guitar pieces in America at the time. Written in open major tuning, they were easily accessible to amateurs (usually in further-simplified arrangements). ↩︎

- Deseret News, 4 April 1931, p. 4 ↩︎

Leave a comment