Emilio Pujol was one of the those remarkable musicians who excelled at many things. He was a great performer, touring Europe and South America to great success. He was a notable musicologist, pioneering the revival of the vihuela (Spain’s equivalent to the lute). He was a seminal teacher, who taught many of the best guitarists (as well as some early musicians) of the century. He was an excellent transcriber — many of his arrangements are still in the repertoire of guitarists and guitar duos. He was also a good composer — many of the works, again, remain in the repertoire today.

Pujol began studying with Francisco Tárrega in 1902, and was arguably the greatest and most influential proponent of the ‘Tárrega School’ and no-nail playing. In 1912 he was, for example, the first guitarist to play the Bechstein Hall (now the Wigmore Hall, an important chamber music venue), and this novel concert — the classical guitar was very seldom heard in Britain at the time — was reviewed in a number of British publication. The Musical Standard wrote that,

‘One can scarcely think of this instrument as a means for the interpretation of high-class music, but rather associates it with serenades and light dance music. In the hands of a capable artist, such as Mr. Pujol, it is, however, very worthy of serious consideration. [… H]e actually played upon this instrument a Bach fugue – finely, too, greatly to the astonishment of most of his audience. […] Some pianoforte solos were given by Count Charles de Souza, who is a good pianist, but the great attraction was the guitar playing, which opened the eyes of many.’1

Amusingly, the reviewer for the Manchester Guardian thought the Bach fugue looked too easy on guitar — ‘child’s play’, apparently! Along with some other reviewers, he preferred Tarrega’s own compositions to the transcriptions of Schubert, Bach et al. He wrote that Tarrega’s pieces ‘are, no doubt, very difficult, and they were played with remarkable ease and ability.’2

Pujol made several recordings in the interwar period (there are also some post-war home recordings that are best avoided; he had mostly ceased performing, had lost much of his facility, and with age he had developed badly shaking hands — his ‘continual vibrato’,3 as he called it). Many of these recordings were with his wife and guitar duo partner Matilde Cuervas, and two of which have survived (from the early 1930s). The audio quality is very poor, but the playing superb:

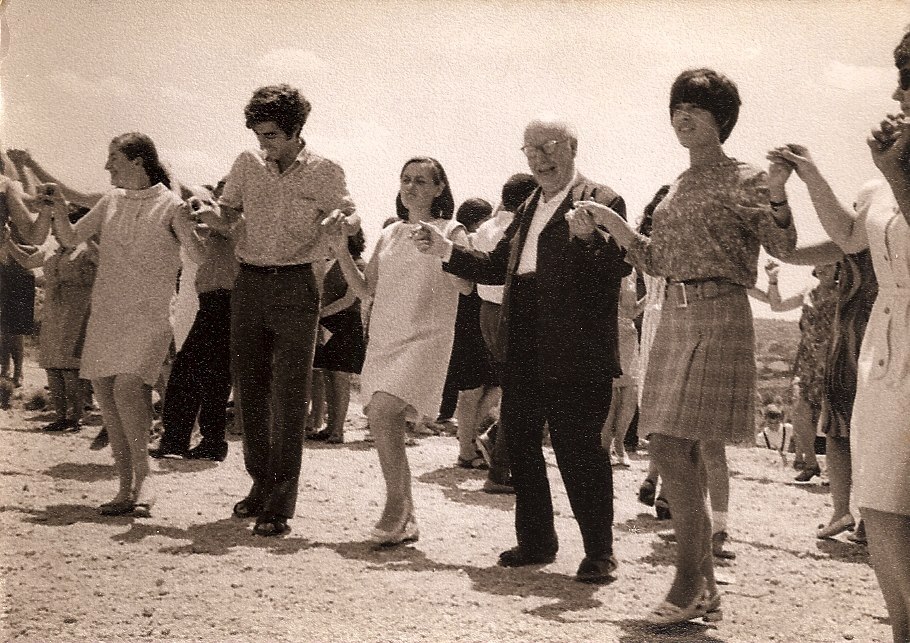

Fine performer though Pujol was, he was perhaps most consequential as a teacher. His four-book Guitar School is a vitally important text, tracing the history of the guitar, offering detailed technical advice, and containing many studies. He had many prominent students, including Manuel Cubedo, Alberto Ponce, and Francisco Alfonso. He was the first to give a guitar course at the Lisbon Conservatoire, in 1946, and continued teaching there for over two decades. He also taught an annual course that was attended by many now-famous figures in the guitar and lute world and beyond, such as Hopkinson Smith, John Taylor, Carles Trepat, Brian Jeffery, and Ned Sublette. (For an interesting account of these courses, I recommend John Roberts Guitar Travels, though it’s a difficult book to find.)

Pujol preferred no-nails, but for the most part he was not dogmatic. He reportedly said that, ‘With nail or without, the sound can be good or bad. It is the bad sound in each case that I object to.’4 He wrote two excellent books that cover the subject. The first is The Dilemma of Timbre on the Guitar — more of a pamphlet, but it covers brilliantly the history and aesthetic questions of plucking the guitar with flesh or nails. The second is his biography of Tárrega (an English edition of which is available on Amazon as an ebook).

As an envoi, here is Rob MacKillop playing beautifully what he describes as Pujol’s ‘masterpiece’. I agree:

Leave a comment