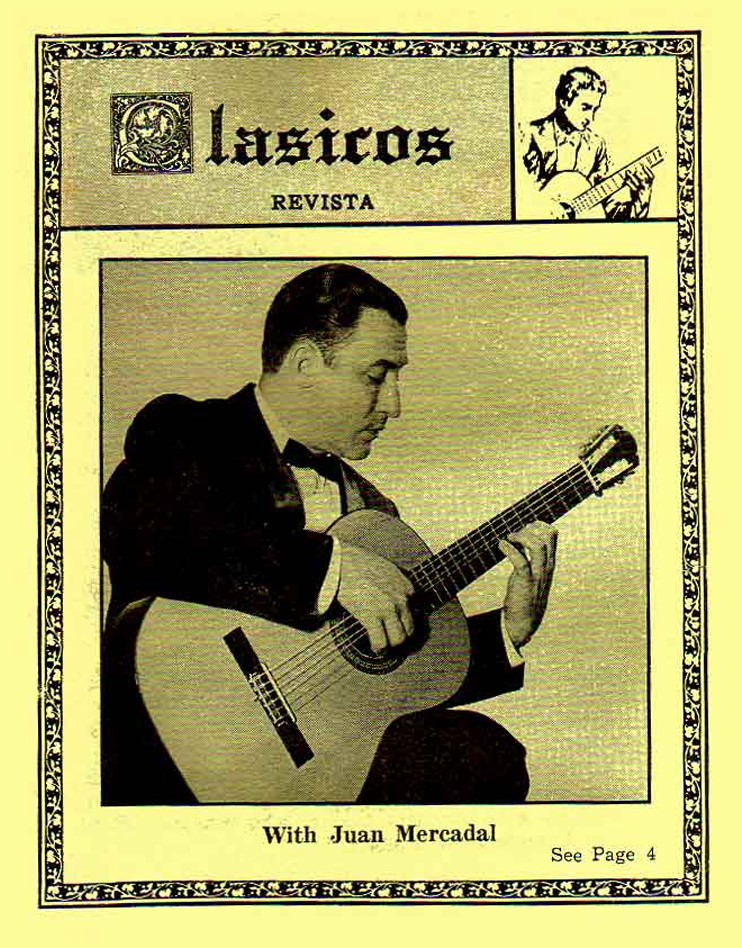

Mercadal was a rather atypical and eccentric guitarist — not just on account of his playing without nails, but also his forcefully expressive style, with an exceptionally powerful stroke. Robert Ruck, Mercadal’s luthier, recalls that

‘Power was the number one thing for him [Mercadal]; first it had to have the power, and then he would consider the tonal properties, playability, and so forth.’

Ruck described Mercadal as ‘macho, cultured, worldly, and gregarious’. He also recalled how Mercadal

‘just didn’t use nails. But his fingers were very callused on the tips, so he got a bright sound, and he had a very powerful attack. He was used to playing with symphonies, without amplification, and he prided himself in having a big sound.’1

One of Mercadal’s students was Manuel Barrueco, who wrote of his teacher:

‘Juan Mercadal was famous in Cuba and he started giving me lessons. He never charged me a dime for anything. He picked me up and took me home. He was a very effusive person. … he was a very “macho” guitarist. You had to see him when he played the first string apoyando the third … and so was his personality, very strong.

[…]

‘He said he had to [play loudly], to play the guitar to be heard, because he also played chamber music. But the sound was without the nail. If you listen to the recording, there is a musicality and phrasing that there wasn’t at that time. And I think it is the objective what I’m saying.

He had a personal way of playing. His playing wasn’t based on the guitar but on the music. He said the guitarists had to develop a way of singing a musical phrase, like a trumpet or clarinet players did.’2

Reading about Mercadal is often good fun. Another of his students recalls that Mercadal

‘would go to South America to play with orchestras and he liked to tell the story of how he would obediently follow the directions of the conductor throughout the rehearsals. But when he was actually playing the concert Mercadal would play at the tempo he wanted. He used to watch the conductor furiously try to keep up with him. “What could the poor conductor do to me?”‘3

Mercadal was born in Cuba and studied with Dr Severino Lopez, who seems to have descended from the ‘Tárrega School’ and may possibly have been an influence on Mercadal’s playing without nails. Mercadal went on to study at the Conservatory Mateu in Havana. According to a 1962 article,

‘In 1960 he ‘refugeed’ from Cuba to Miami, Florida, with his wife and two small children, and worked eight hours a day for an airline, practising his guitar for three hours every evening — after the youngsters had been put to bed.

‘He was given his ‘big opportunity’ on March 4th, 1961 when International Cultural Exchange presented him at the White Temple Auditorium, Miami. His sincere and sensitive artistry won tremendous applause from the audience and praise from the critics.

‘Even before he left Cuba, Juan Mercadal had given recitals in Brazil and other South American countries. In fact, the Brazilian composer Radames Gnattali (b. 1906) wrote a Guitar Concerto specially for him. He performed it with the Brazil Symphony Orchestra in Rio de Janeiro.‘4

A 1963 review of one of his concerts:

‘As always, Mr. Mercadal’s performance was spell casting, holding the audience almost breathless throughout the full length of the Sor work. He has the widest range of dynamics of any guitarist we have ever heard, the most delicate pianissimo, the finest legato and the loveliest tone.’5

He performed across South America, aided by his job working for an airline company, which he took to support his family. After migrating to America, he set up a flourishing guitar school at the University of Miami, one of the first of its kind. He performed with many orchestras, and was even asked to play the national anthem at the Orange Bowl in Miami, in front of 80,000 spectators.6

On the subject of nails, Mercadal definitely played without nails until at least 1965. Asked in a 1965 article if he plays with fingers or nails, he replied, ‘I use my fingers, so I consider this best, but again, this is also a matter of opinion.’7 All those quoted above refer to Mercadal playing without nails, and well after 1965. However, there are contradictory accounts from two of his students. One stated that he ‘begrudgingly grew his index and middle nails’ sometime after recording the album At Vizcaya (1964/65).8 Another student, in a 1981 dissertation on Mercadal, wrote that Mercadal used no nail on his thumb or index finger — moreover, that he was unable to grow his index finger nail — but did use nails on his middle and annular fingers.9 Assuming one of these is accurate, it would mean — very oddly and one would think almost impossibly — that he had two fingers with nails and two without. My ears cannot discern any of this in the surviving recordings, and I’ve heard from others who recall him playing without any nails in the 70s and 80s, so I’m not sure what to think. I will try to find out more and remember update this page accordingly. If it is true, I suppose it would be entirely in keeping with Mercadal’s unique character!

Here is a recording of Granados’s La Maja de Goya, in which he is definitely playing without nails on all his fingers!

- Interview with Robert Ruck, https://www.guitarsint.com/guitar_maker/Robert_Ruck ↩︎

- Manuel Barrueco, ‘Master Series: Manuel Barrueco 2013’, interview by Fernando Bartolomé Zofío, July 2013, https://modernguitarensemble.blogspot.com/2014/01/master-series-manuel-barrueco-2013-ie.html ↩︎

- Gary Rodriguez, ‘THE PASSING OF A CONCERT GUITARIST AND TEACHER, JUAN MERCADAL OF HAVANA, CUBA AND MIAMI, FLORIDA’, https://www.oocities.org/vienna/5702/mercadal.html ↩︎

- Guitar News, 64 (1962), p.14. ↩︎

- Guitar News, 74 (1963), p. 20. ↩︎

- Mark Roger Switzer, Juan Mercadal: A Biographical Sketch and a Study of His Pedagogical Process (University of Miami, 1981), p. 38. ↩︎

- Guitarra Magazine, 3.17 (1965), p. 5. ↩︎

- Kenneth Keaton, ‘Masters of Guitar 3: Cuba 1955-1965’, American Record Guide, 80.6 (2017), pp. 216-217. ↩︎

- Switzer, p. 62. ↩︎

Leave a comment